Ran into an old acquaintance the other day who told me excitedly that they were now, “in renewable energy.” “Have you met my mum?” I answered. They were somewhat baffled but I was serious. Whatever force is driving my 95-year-old mother into another winter, it seems more reliable than the sun.

The obvious and traditional answer to this apparent mystery of maternal power would be food, and the time-honoured process of metabolism by which it is converted into energy. Except that last time I made dinner mum said, “I’m stuffed” and fed the rest of her portion to my brother’s dog. The canine connection is apposite since the miraculous energy puppies access from a handful of dry biscuits seems to stem from the same mystical font as my mum’s late life flair for transmuting the occasional mouthful of this and that into almost a century of survival.

OK – she isn’t chasing any sticks, but it is still remarkable. Until last month I was part of a trio of friends, all of whom had surviving mums in their mid-nineties. Over the course of a week, a week we now refer to as ‘Mumageddon’ both my friend’s mum’s died. It feels useful to note how upsetting I found this, and I think that was because my own mother’s mortality is much on my mind – or perhaps I should say I am constantly maintaining my defences around it – whereas the passing of my friend’s mums, one in particular, really took me by surprise. So I am alone then – last mum standing – though not as alone as I will be.

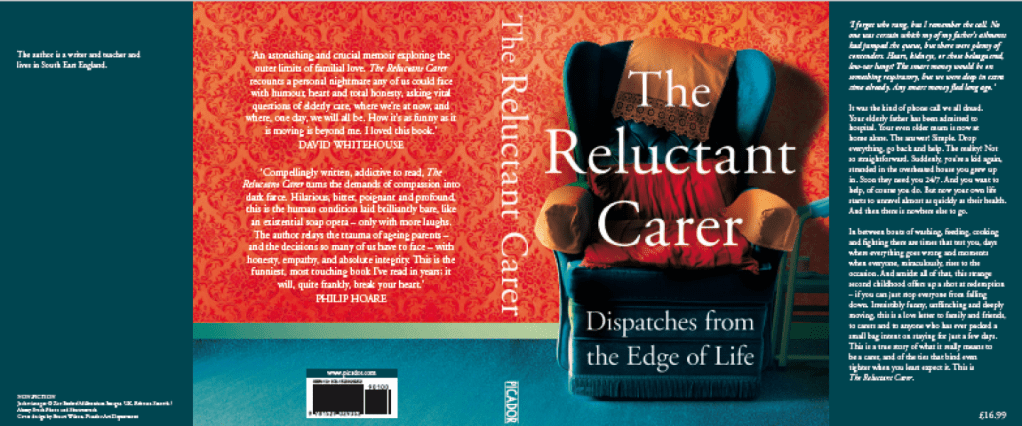

Meantime I take mum’s survival and relative stoicism as a lesson in itself – if she can do this, so can I. In an effort to get my head around where her head is at I have been studying Oliver James’ book ‘Contented Dementia.’ Contented Dementia: A Revolutionary New Way of Treating Dementia : 24-hour Wraparound Care for Lifelong Well-being : James, Oliver: Amazon.co.uk: Books Since my own book came out https://www.panmacmillan.com/authors/the-reluctant-carer/the-reluctant-carer/9781529029390 James’ has been frequently recommended to me, and so, despite some resistance to abandon my own ‘make it up as you go along’ policy I decided to buy the book and take some advice.

At the book’s opening James outlines three points as the foundation of his approach, one of them is “always agree with everything they say, never asking questions.” As you will have instinctively understood, this is as not as simple as it sounds. “We haven’t seen much of Dad lately,” says mum. Where once I might have pointed out gently that her husband – my father – passed away two and a half years ago, I adopt the new strategy instead and answer. “I haven’t seen him, and I’d be worried if I did.” This works, Mum laughs, and does a plausible impression of seeing a ghost. This would not have been the case if I had simply set her straight, however gently. So this method is much in favour now, although compared to some of the allegations against reality that I hear these days – that was an easy one.

The book also explores how dementia gets in the way of forming new memories. I realise that something similarly dementia-like is happening to me thanks to mum’s carer’s addiction to greatest hits radio. The non-stop eighties soundtrack that accompanies my interactions with my parent in her nineties adds the emotional complication of making me feel as though I am sixteen. This is amplified by the fact this is taking place in the same house I lived in when I was sixteen. So I do the elderly stuff while another part of me is convinced by music that I am going out for the evening. It is an odd juxtaposition until I realise what teenage and present predicament me have in common is that we are both trying to work out what women are thinking. I would page Dr Freud but I think he’s busy. I must make do with Dr and the Medics, and the beat goes on.