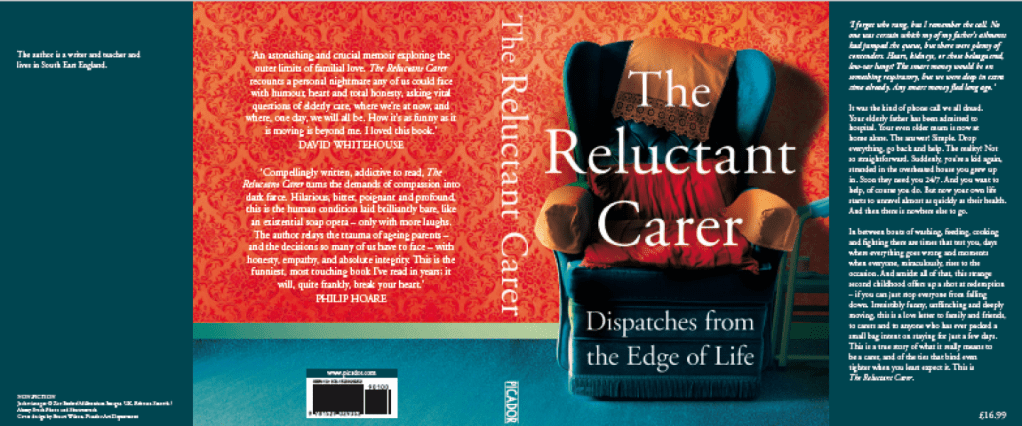

Things have changed since I put my name to all this back in the summer. One of the sadder outcomes is that I find it much harder now to write about my mother. When she was the mother of someone nameless that was OK. Now that I am really me and she is her, I feel this hesitation, I am more careful, and there’s that word again, care. Sometimes I beat myself up for writing the book anonymously https://www.panmacmillan.com/authors/the-reluctant-carer/the-reluctant-carer/9781529029390 but if I am honest then I don’t think I could have been that honest any other way. It had to be, and whilst she thrives, which in her way she does – amazingly – there will be less I can say.

Instead perhaps I can give a shout out to another significant woman, Melanie Klein. Klein, for my money, is one of the great innovators of analytic thinking after Freud, and perhaps the foremost visionary of early, pre-verbal, infant experience and how it shapes us for the rest of our lives. I bring her up here because her thoughts on love and its (for her) intrinsic relationship to what we consider our more destructive instincts and more sorrowful feelings was of great solace, liberating even to me when I was wondering why my emotions where such a conflicting mess at times whilst, ‘caring.’

I included her in the Guardian article in July https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/article/2024/jul/06/reluctant-carer-to-redundant-carer?CMP=twt_b-gdnsaturday but it was (rightly, I think) edited out. Here though is what I wrote in case you, who come here or subscribe because you are interested in these things, find it useful:

“What is it then that we are running away from? Like much of our world when examined honestly, the caring role will not reduce to the simple good/bad splits of contemporary inclination. More than Freud it is Melanie Klein, one of his foremost successors, whose work sheds the most light on this kind of denial. She asserted that the urge to split things into good and bad was our most basic inclination under pressure, an instinctive flight from reality. Klein also said directly what dramatists had been exploring for centuries, that anxiety, guilt and aggression were, “among the essential and fundamental ingredients of the feelings we call love.” The long, slow, death-in-life of a parent is likely to elicit all those things. Part of what we are fleeing is the uncertainty. “When”, we ask ourselves, “will this end?” The corollary of this longing to know is to anticipate the death of your loved one, and if that logical thought replays as an accusation [you are now thinking ‘bad thoughts’] – then the ensuing guilt becomes another way to bid your own wellbeing goodbye. The discomfort around this is such, I would speculate, that some proportion of the violence that does sometimes happen in these situations is directed against that inner turmoil as opposed to the person prevailed on [you’re fighting your own feelings – not your ‘foe’]. As a close family member, you are both the best and the worst person for the job. You know just enough and far too much. And when you give up the job, there is a lot to reflect on.”

Her quote in my quote there comes from Love Guilt and Reparation, which is a collection of her papers. Far from an easy read, but credit where it’s due. Speaking of easy reads, I still find I need an outlet so I am going to post things here going forward:

(1) Precise Instructions For Everyday Life | Michael Holden | Substack

Please do sign up if you want more of my writing – although there will be less of mum. More news here when we get it.

With thanks

MH