I am upstairs on the phone to a solicitor, attempting to reckon and repair the wreckage of my former life. The billable minutes are clicking toward billable hours when the sounds of parental discord rise from below, like the house band striking up a familiar number in some place you can’t believe you still visit. A life you thought you’d left long ago. But no…

The telephones at my folks, like all else here, are far from modern. A botched network of cordless handsets that seldom make it back to the correct cradle, each with a background hiss that makes everything sound like AM radio. Improving this is somewhere on my list of things to do. The solicitor’s voice, which I (in some version of denial) struggle to make sense of on a good day, is relegated even further into my mind as I listen instead, just as I did as a child, to what my parents are squabbling about. In this case , trousers.

Mum’s relationship to ironing could be the subject of a separate essay, but the essence of today’s dispute concerns Dad (who I have never seen iron) asserting that some trousers she has ironed for him (in which he will go nowhere, see no one but her or me, and do nothing but sit down) should have a crease in them. Mum says this cannot be, “you cannot have a crease in cotton trousers.” My father’s answer, which comes at a special volume, several notches higher than the one necessary to get my mum to hear you at all, peels through the house– “I CREATE ONE!”

Given his size and wellness an utterance of this dimension is an achievement. The dying body is, one presumes, preserving these powers for some desperate and definitive address or plea. That it should arise instead from such apparent trivia is but the everyday pathos of domestic life. Something and nothing at the same time.

The creation of which he yells concerns his trouser press, an artefact (now inaccessible upstairs) which speaks to both its owner’s precision, care and vanity as much as to what I assume (given his military experience) must be unwillingness rather than inability to wield an iron.

The more I think about it, the more it becomes clear that a further examination of the role of ironing in life here is necessary. Mum can barely lift the iron, the board is taller than she is now and yet, unless physically restrained she will haul these implements into position and iron something. Singing as she does so, sometimes. Whether you see this as a reflex of servitude or a state of studied and deserved grace will reflect perhaps some political position (I am of the latter party), but again, more on this to follow. I only hope that you can bear the tension.

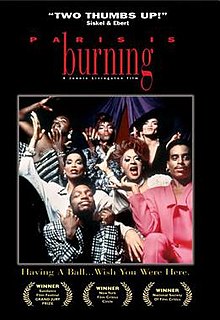

As all this drifts through my mind, my solicitor takes pity and offers to end the call, I concur. I think on my father’s sartorial and presentational concerns, on quite how long it will take he and I sometimes to get him “ready” for not much at all. When we do go out, the stakes rise, the raiment laid out and double-checked the night before. A trip to the doctors, a funeral, a pub with good food, each rendered like a state occasion. I have come to find this a helpful way to think about it. I serve the last royals of a failing state. Ceremonies are all we have left before the people (in this case death, but also taxes) seize the palace. Here we go. Paris is burning.**

In the morning rituals the angle of the sun reveals plumes of perished flesh erupting from his shins as I pull up his trousers. He is crumbling, monumental. We are told that dust is dead skin, but it’s not until I see this that the constant transaction between who we are, what we’re made of and where we are going becomes quite so clear. On one level there is revulsion, on another beauty. If the light is right you can see the particles falling and rising in the air and catch the sublime in it. All my life I have been told I think too much but at times like this it seems to save me. I wonder if he sometimes sees the same, I believe so. Occasionally I think the only difference between us is that I have found a way to get these things out, to express them, even if it is to strangers. I wish we talked more. Instead I pull the unsaid about me like a blanket. I have no idea how I would look without it now, or how to put it down.

*Not quite true. Once, you were the taken-care-of.

** I would commend anyone interested in dressing to the seminal documentary of the same name:

I am trying to remember when it became normal here for someone to be naked. It wasn’t like there was a meeting. One day, and this must have been back when dad could get upstairs, nudity became unremarkable. It happened on the landing.

I am trying to remember when it became normal here for someone to be naked. It wasn’t like there was a meeting. One day, and this must have been back when dad could get upstairs, nudity became unremarkable. It happened on the landing.

As I ferry dad back to his seat, I ascertain, in short order, what has gone down (and it is in these kinds of mindless crises that I really come into my own). With mum’s deafness it is essential that the TV has subtitles or it has to be on at a volume that could destroy a passing bird. As it is, it is often so loud they should be in hi-viz jackets. Anyway, the subtitles went off and the old man has had to call the service provider to turn them back on. Somehow this has a) not been accomplished and b) evolved into an attempt to make him pay even more for watching television.

As I ferry dad back to his seat, I ascertain, in short order, what has gone down (and it is in these kinds of mindless crises that I really come into my own). With mum’s deafness it is essential that the TV has subtitles or it has to be on at a volume that could destroy a passing bird. As it is, it is often so loud they should be in hi-viz jackets. Anyway, the subtitles went off and the old man has had to call the service provider to turn them back on. Somehow this has a) not been accomplished and b) evolved into an attempt to make him pay even more for watching television.